Time is one of my favorite subjects. The reason being it’s highly mysterious and absolute nature. It give everything a reference frame. How else on earth would have you said when a thing actually occurred. It actually gives even the rest of the three dimensions a reference frame. Newton put forth the theory that nothing in the Universe is absolutely stationary, no not you standing still, because the earth is spinning, and not the earth since it is revolving around the sun. The sun goes round the Milky Way (our home galaxy) once in every 225 million years. Not surprising now, the Milky Way is not stationary itself, but moving towards Andromeda (our neighboring galaxy) at about 400,000 km/h. Point here is that, you cannot determine the absolute position of an object anywhere in the Universe by just giving the three physical dimensions. It simple doesn’t work where there is no frame of reference. Then how do you tell your position? You tell it in terms of space-time. The fourth dimension, that is of the time can be in any unit of time. We can actually convert the first three coordinates in terms of light-seconds which is distance in terms of time taken by the light to travel the same distance.

But well, time is in fact, only absolute to a person at a particular position. Time is well affected by gravity, the same way light is. This is to simply say the time seems somewhat slower near a body of high mass, like the earth, or a black hole for some serious observations. We don’t actually see these differences in our routine life since they are too small in case of the Earth (Earth is not as dense as it should be for practical effects of delay in time to be observed by us). But there are applications on Earth that require precise measurement of time, and one such application is the Global Positioning System, the GPS in almost every phone these days. It relies on three geostationary satellites that measure the exact time taken for the receiver to reach them, creating a triangular plot, estimating the position of the receiver on the surface on the planet within a couple of meters accurately. These satellites are feed with the slightly wrong time after some unspecified interval, just so that it can adjust with the ‘slower’ time on the Earth’s surface (on account of the larger mass of Earth affecting the bodies near to it to a larger extent and also due to the relatively faster time on these satellites on account of their speeds due to special relativity).

There is another interesting thing to note here. How can you say if you are experiencing a slower version of time than you did some time in the past? You can’t. The reason is, ‘slower’ and ‘faster’ time are for the observers that are experiencing a relatively ‘faster’ or ‘slower’ time. So it is all relative. Talking about time in the context of speed of light, we come to an amazing theory by Einstein. Einstein proposed that the speed at which light travels is absolute and does not depend on the relative speed and position of the observer. To put it simply, imagine you are traveling on a highway at 60km/h. Another vehicle traveling at 70 overtakes you. For you, the relative speed of the other vehicle is 10km/h (which is, 70-60=10). This is how we expect things to behave right? Of course. But things change as one approaches the speed of light. See that light doesn’t behave the same way our highway example cars did. However fast you’re traveling, light will still be 300,000km/s faster than you, even if you are actually doing 290,000km/s (which is just about impossible for a body of large mass like us, but certain elementary particles can achieve those speeds). This can be considered the universal speed limits. So what happens when some particle tries to break this barrier?

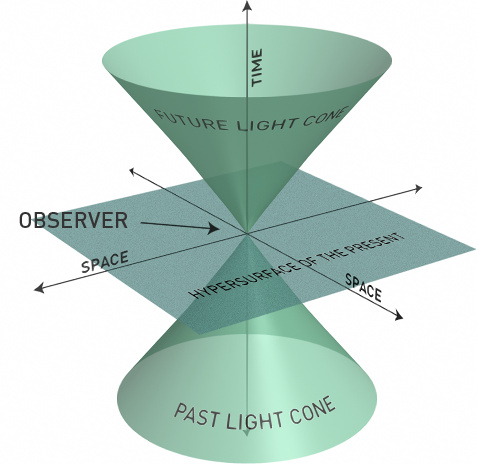

For understanding this, let us consider the cone of light. When a particular event occurs, it sends out light (or radiations) in all possible directions. This is like throwing a pebble in a pond of water. It spreads in all possible directions and it’s size increases every instant. The outermost wave is the wave initially created by the pebble itself. Now think of this as light. An event occurs and light from that event spreads in all possible direction. Considering time on y axis and space on x, we can imagine a cone getting created.

Now when something occurs, you don’t see it immediately, until the light from that event hits your retina. Consider the sun, for example. It is at a distance of about 149 million kilometers from the earth. Light takes about 8 minutes and 20 seconds to travel this distance. This is the reason the sunlight you’re seeing now is about 8 minutes and 20 seconds old. Which means that it takes the cone of light from sun, 8 minutes and 20 seconds to reach us, and make us aware of it. Still, considering the distances of other planetary objects, sun is quite close to us. Our nearest star, Alpha Centauri is at a distance of 4.3 light years from us, that is, the cone of light takes 4.3 years from Alpha Centauri to reach us. Since it is the cone of light, not surprisingly, it travels outwards at the speed of light.

Back to our original question, what if some particle tries to break the barrier of speed of light? If that happens, it will move from inside the cone of light of one event to outside of it, effectively seeing the time from the past, hence ‘traveling in the past’. But is that possible? No, according to the special theory of relativity. Since speed of light is absolute to the reference frame it is measured in, nothing can reach it (the mass of an object goes on increasing with increasing velocity. Close to the speed of light, the mass of the object is infinity and pushing an object of mass infinity is not possible). This was even proved by an experiment (Michelson-Morley experiment). This theory was consistent with the observations and most other theories, but Newton’s gravitation theory. If everything travels at speeds less than or equal to the speed of light, how do we explain the effects of gravitation on distant planets and stars instantaneously. Does gravity travel at infinite speeds, as opposed to relativity, which states that gravity travels at speed of light, which is again, not in accordance with solar system observations? Maybe.

Einstein spent a great deal of time trying to find a theory that would be consistent with both, the theory of relativity and the theory of gravitation. Finally he came up with something called the general theory of relativity. This theory suggested that the force of gravity doesn’t act like normal forces but it acts on the ‘space-time’ fabric, bending it in proportion with the relative energy and mass of the body. This suggested that the bodies revolving other bodies like the moon and earth are not traveling round the other body, but actually taking a straight path in the space time fabric which is 4 dimensional, and they only ‘appear’ to travel in elliptical orbits as we see them in 3 dimensions. This was a revolutionary suggestion. It implied that time, light all traveled curved path near objects of high mass or energy. That did, infact explained why time appeared slow near the surface of earth and faster from space, and also, how are we able to see stars that are just behind the sun even if a straight path to them would not be possible for light to take.

Now as we look at where this article started, yes, I was all wrong. I knew there was nothing as absolute space, but as it turned out, there is nothing as absolute time as well. Interesting though, isn’t it?

Time in the world of computers!

Computers happen to be my most favorite subject after astrophysics, so how can I let this special opportunity go without playing around with time functions in C++. To be honest, I had been on this time thing from about 2 weeks. I needed to calculate time precisely for looking at the efficiency of sorting algorithms. Not surprisingly, computers are way too fast for calculating time in seconds or milliseconds. To see the difference in time taken by two algorithms for sorting a set of 50 random numbers, you need to measure time in nanoseconds, at the least microseconds. Although I had trouble (a lot of trouble, in fact) in getting the time functions to work for me, I finally succeeded in getting nanosecond level precision without any extra props, just my PC and g++ compiler.

Starting from the first thought that came to my mind, get some C++ reference for built in functions. time() from <ctime> does a great job to fetch the number of seconds since 1st Jan, 1970,

but not good enough for me here. I knew that the bash command ‘date’ can be used for my purpose, but I couldn’t see a way to get the output of the command to my program back. I did some over smartness here. I executed the system(“date +%s%N > text”) which wrote the current timestamp upto the nanosecond to ‘text’ file. Then copy that time by reading the file into an unsigned long long int (since it is 19 digits long). Then after the calculations, repeat it again and subtract the initial time from the final one. A bit long cut, but I hoped it to work.

When I ran this code, it took, surprisingly 18+ milliseconds, or in particular 18649390 nanoseconds. And to be clear, I haven’t even included any code whose performance benchmarks I had to measure. This is the base time, LOL. Thinking about it for a second, algorithms store variables in cache, because RAM is not fast enough and I tried to write and read from the hard drive. That is so damn clever of me!

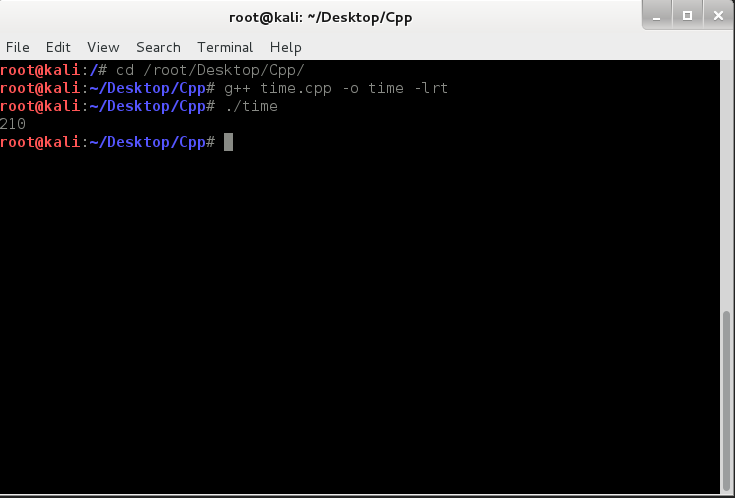

Pun aside, Now it was time to get help. Many stackoverflow posts and a good guy’s guidance later, I finally got the clock_gettime() from <sys/time.h> to work. Yes, now I was getting some pretty good numbers and I could see the difference when I added more stuff to the code.

Executing the raw code without any load gave some results I was hoping to see.

210 nanoseconds which is fine for a code that does nothing. This will serve all of my purposes, and should do most of anyone’s who is up with sorting algorithms.

PS – I tried hard to find good sources for information on the first part of this article, still if there is any mistake, don’t hesitate to notify me.